ChatGPT was released by OpenAI (November 2022) to the wider world (though not everyone can get onboard) with little guidance, little fanfare, and a subtle tease for people to explore. Potentially this ‘you tell us what you think it is’ approach is part of the broader plan, potentially a marketing exercise helping it to cross 100 million users by this January 2023 or perhaps to allow us to train the model by our interaction. Now it seems that AI tools are popping up everywhere doing many different functions to varying degrees of success. A list of ChatGPT extensions/alternatives can be found here. There are also image AI tools such as Dall-E, Midjourney, Stability AI.

Some of the well documented controversy of these tools has made AI the word on everyone’s lips. For education this has grown fears of the tool being misused for plagiarism or amounting to ‘surface learning’ (Marton and Sajo 1976) and through to it taking away educators jobs. Leading to several education organisations, districts banning the use of AI. A good example of this confusion can be seen in schools in Victoria first banning them then setting up a study to explore them within a few weeks.

While not placing these fears aside completely, I wanted to explore the tools in terms of support education from a slightly different perspective in terms of supporting education from a teacher perspective.

We have all been there as educators, not enough time in the day to get everything done and focus on the things that mean something to us, actually teaching. While we hear from the rest of the world that we have an easy job and long holidays! Its simply not the case ,an educators working week is made up of a number of duties and tasks, teaching being what feels like an ever decreasing element of our work week.

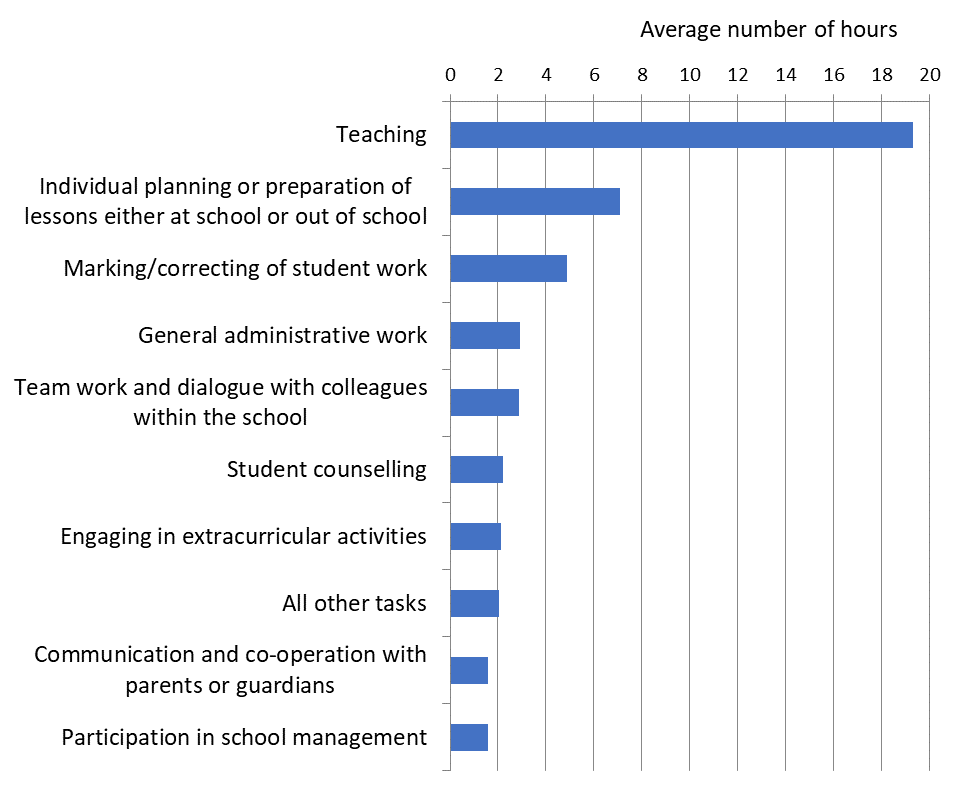

According to an OECD report in 2014 (TALIS) “The overall average time spent teaching is 19 hours per week, ranging from 15 hours in Norway to 27 hours in Chile”. The report offers a breakdown as follows: –

Source: OECD http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888933042029

Building on the thought that AI tools, much like word processing, excel, student information systems and even the calculator can improve efficiency through automation and that if AI tools were used in a targeted way could they give back time to teaching. In short teachers can spend over a third of their time on administrative tasks and less than two thirds of their time working directly with students (Darling-Hammond, 2010).

Could AI provide not only the ‘magic bullet’ of a reduction in administrative tasks and potentially improve instruction, by either providing relieved time or from supporting instructional practices.

From my own first experience of ChatGPT as an educational tool “why is the sky blue”, I had my first play around, this led me to dive into this a little deeper with my educator hat on.

A recent report in education week reported that “In our survey of teachers, we also asked them to rank duties they think AI robots could replace to help them do a better job teaching. The top-ranked response (44 percent of teachers) said “taking attendance, making copies, and other administrative tasks,” 30 percent said “grading,” and 30 percent said “translating/communicating with emerging bilinguals.”

One of my first concerns though impressed by the ‘parlour trick’ nature of ChatGPT, was the apparent lack of quality of the results, inconsistency of the responses, the interface and what seemed at times to be invalid information.

So I set about conducting a few slightly random exercises to see if ChatGPT could support educators, not in the classroom but in other ways. Examples of these exercises can be viewed in the following posts.

Child on a beach – my journey with ChatGPT as a storyteller, primary lesson planner and teacher trainer.

A letter to a parent – could ChatGPT help to write administrative letters.

E=mc^2 – ChatGPT produced what looked on the surface a fairly traditional lesson plan, assessment strategy and resource list.

Perhaps we could use a model to assess these

What I have learnt is that with ChatGPT there are challenges in a number of areas of the model “Information Quality” (AI responses can mostly be distinguished and are at times formulaic), “System Quality” (it is quite a bare bone tool) and “Service Quality” (not that accessible, its often down). There are also questions related to the Intention to Use, general User Satisfaction, however if we can imagine the net benefits what automation of the administrative tasks would look like for a teacher, this may evolve.

In short, my general feeling is that for some administrative tasks ChatGPT is useful, be not reliable or credible. There would need to be further evaluation of process-oriented approach vs the product-oriented in most instances of use “The process-oriented approach evaluates how a skill is performed, whereas the product-oriented approach evaluates the outcome of the skill performance” (Payne & Issacs, 2017). These AI skills vs Human skills would need to be evaluated and contextualised against D&M Model or similar. Thus, the automation here might suit the generation of a generic letter or lesson plan but not a bespoke one. This also should be considered with the thought that “Digital technology does not alleviate teachers’ work” (Keri Facer and Neil Selwyn, 2021). AI will potentially create yet another development skill set or barrier for teachers to overcome to achieve these non-teaching efficiencies and the result might be something like “Winning a Pie-Eating Contest and the Prize is More Pie” (source not known)

If I look into a crystal ball, I can also see where these tools may be headed when paired with other education ecosystems “potentially creating new kinds of dependencies and technological lock-ins” (Williamson, Macgilchrist, Potter, 2023). This further platformisation of education invokes the slightly more sinister side of these rapidly developing ecosystems as put very well in this article “Another day, another exhortation to join an ‘ecosystem’ that’s anything but.” (Maria, 2022). Therefore, the release of AI and its impact on education may have its uses if it is on rails, but AI is potentially not the only challenger to the traditional models, modes and ecosystems of education.

There are many styles of other platforms or ecosystem approaches education such as Minerva including not only digital approaches but differing pedogeological approaches these central command style approaches can also be found in international school groups like Sabis. Like Minerva and Sabis in the Bridge International Academies materials are provided centrally “representing a form of pre-packaged and commercialised pedagogy that is uniform and consistent from one cookie-cutter school to the next, whether that be in Kenya or Nigeria or India” (Riep, 2017).

We may also find a situation where we are not only “education rentiers” (Komljenovic, 2021), but the rentiers of knowledge generation and presentation. The value of the ‘prompt’ to AI is already being commoditised with marketplaces such as promptbase, participants can purchase a pre-built prompt or design and sell a prompt as a ‘prompt engineer’, there are already prompts being sold for a course outline, I created some education examples of my own based on my own ‘prompt engineering’. Will AI become another “Market Device” (Riep, 2017, Callon, Millo, and Muniesa 2007), where in the example of OpenAI the tokenisation of pricing related to the provision of words (Knowledge Presentation) will make us rentiers of words, thus a form of currency in knowledge acquisition..

These conclusion topics are probably too large for a single posting, I am open to further collaboration or discussion..

References and further reading

References

- ChatGPT Stats – https://www.demandsage.com/chatgpt-statistics/

- Chat GPT Alternatives – https://beebom.com/best-chatgpt-alternatives/

- “On Qualitative Differences in Learning: I—Outcome and Process”

- OECD (2014), TALIS 2013 Results: An International Perspective on Teaching and Learning, TALIS, OECD Publishing.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2010). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future

- Teachers, the Robots Are Coming. But That’s Not a Bad Thing https://www.edweek.org/technology/teachers-the-robots-are-coming-but-thats-not-a-bad-thing/2020/01 (suggested reading by Huw Davies, in discussion forum

- William H. DeLone, Ephraim R. McLean, (1992) Information Systems Success: The Quest for the Dependent Variable.

- Payne VG, & Isaacs LD (2017). Human motor development: A lifespan approach. Routledge

- Keri Facerand Neil Selwyn (2021) Digital technology and the futures of education –towards ‘non-stupid’ optimism.

- Ben Williamson, Felicitas Macgilchrist & John Potter (2023) Re-examining AI, automation and datafication in education, Learning, Media and Technology, 48:1, 1-5, DOI: 10.1080/17439884.2023.2167830

- Maria ‘Your platform is not an ecosystem’, 2022 https://crookedtimber.org/2022/12/08/your-platform-is-not-an-ecosystem/

- Curtis B. Riep. 2017 Making markets for low-cost schooling: the devices and investments behind Bridge International Academies